THE RIGOR OF ANGELS: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality, by William Egginton

Chances are, if you have ever heard the story of Solomon Shereshevsky, you haven’t forgotten it. Shereshevsky’s powers of memory were so remarkable that in 1929 he gave up his job as a journalist in Moscow and joined the circus. He could recite lists of numbers, poems in foreign languages, even strings of random syllables that were called out to him from the audience. His world was abundant in particulars, brimming with imagery and sensations. When asked to share his understanding of the number 87, he said he envisioned it as “a fat woman and a man twirling his mustache.”

But his extraordinary gift was also a terrible affliction. Shereshevsky couldn’t generalize from the barrage of specific inputs he experienced. Communicating with others was exhausting. Forgetting something wasn’t a matter of passively letting it slip away into oblivion; he had to actively destroy it in his mind. If each and every thing you encounter is charged with a singular meaning, gathering those bits together into a coherent picture becomes impossible. In contrast to memorization, remembrance requires the slight blur of abstraction. As William Egginton writes in “The Rigor of Angels,” a “perfect memory” can begin to resemble “total forgetting.”

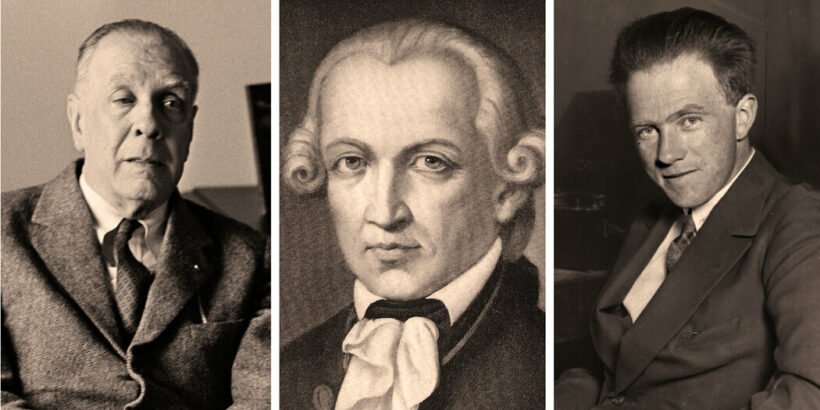

Shereshevsky makes only a cameo appearance in Egginton’s mind-expanding book, but his plight opens up a portal into thinking about space and time and our place in both. Challenging, ambitious, yet also elegantly written, “The Rigor of Angels” explores nothing less than “the ultimate nature of reality” through the life and work of three figures: the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges; the German theoretical physicist and pioneer of quantum mechanics, Werner Heisenberg; and the 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Egginton, a literary scholar at Johns Hopkins, brings these three very different men together in one book because they all shared something unusual. They resisted the temptation to presume that there was a reality, out there, that was completely independent of our attempts to know it.

The formidable creativity of their work was, as Egginton puts it, a matter of “letting go” of what we assume must be real. This turns out to be exceedingly difficult to do. Even Albert Einstein, whose name is synonymous with genius, had trouble doing it. In 1915, he did let go — though only up to a point. His theory of relativity required him “to disregard what everyone knew about space and time in favor of what the data were telling him,” Egginton writes. But Einstein’s own calculations were telling him that the universe was either shrinking or expanding, and so he inserted a cosmological constant to maintain the fiction that the universe (which is in fact expanding) remained a constant size.

In the 1920s, Einstein sparred with Heisenberg over quantum mechanics — which unsettled what physicists at the time took to be “the ultimate nature of reality.” Einstein’s theories of relativity could explain the workings of the universe at the grand, cosmological scale, but Heisenberg found something very different at the subatomic level. Egginton describes how the “smooth continuity of matter’s movement” is replaced by “violent quantum fluctuations.” Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle was especially offensive to Einstein; Einstein refused to accept that particles like electrons would follow a distinct path only once they were observed. In Benjamín Labatut’s recent genre-bending nonfiction novel “When We Cease to Understand the World,” Heisenberg is memorably described as someone “who seemed to have gouged out both his eyes in order to see further.”

Egginton gestures at connections between the work of Heisenberg, Kant and Borges, between physics and metaphysics, fiction and fact. All three men were fascinated by paradox, or antinomies — situations in which “both options seemed at once absolutely necessary and utterly impossible.” Each realized that such dilemmas arise when we mix up different modes of thinking. In Zeno’s famous paradox, Achilles will never catch the tortoise who gets a head start if we define the race in terms of a distance between them that is infinitely divisible into ever smaller slices. But of course, in an actual race, Achilles will eventually catch the tortoise; the paradox emerges from how we imagine the race in the first place.

This is a book about the tiniest of things — the position of an electron, an instant of change. It is also about the biggest of things — the cosmos, infinity, the possibility of free will. Egginton works through ideas by grounding them in his characters’ lives. Heisenberg’s scientific research was so bold, yet his political engagements were curiously cautious and passive; in the 1930s, he seemed unable grasp the monstrousness of the Nazi regime. But Egginton says that Heisenberg’s behavior may not have been as paradoxical as it seems. Heisenberg’s “preternatural patience with trying things out” perhaps expressed itself in “a failure to recognize an actual evil in the world and react strongly against it.” The mode of thinking that made him such a brilliant scientist was, Egginton suggests, inhibiting his ability to understand what was happening around him.

In the example of Shereshevsky — not to mention in Borges’s story “Funes the Memorious,” about a young man who was similarly afflicted by powers of total recall — being so preoccupied with details came at the expense of apprehending the bigger picture. Borges describes Funes as “not very good at thinking. To think is to ignore (or forget) differences, to generalize, to abstract.” Yet thinking can also get us into trouble, Egginton shows. Sometimes we can become so enamored of our ideas that we project them onto the world, mistaking our own mode of thought for something as grand as “God’s plan.”

The beauty of this book is that Egginton encourages us to recognize all of these complicated truths as part of our reality, even if the “ultimate nature” of that reality will remain forever elusive. We are finite beings whose perspective will always be limited; but those limits are also what give rise to possibility. When we choose what to observe, we insert our freedom to choose into nature. As Egginton writes, “We are, and ever will be, active participants in the universe we discover.”

THE RIGOR OF ANGELS: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality | By William Egginton | 338 pp. | Pantheon | $30

Jennifer Szalai is the nonfiction book critic for The Times. More about Jennifer Szalai

Source: Read Full Article